4 Key Questions for the NBA’s Homestretch

Celtics regular-season dominance, Zion unleashed, a tight MVP (and 1-seed) race, and an abysmal bottom of the league.

Welcome to the final month of the NBA season! Exactly four weeks from today, six teams in each conference will secure playoff berths, with the play-in tournament days from kicking off the postseason. When the Denver Nuggets won the championship last June, I wrote about how the NBA had entered its “Age of Parity”. This season further solidifies the notion that another uncertain chapter is about to unfold.

How many teams will enter the postseason with a sincere belief that they can win the championship? Boston, Milwaukee, and the Zombie Miami Heat in the Eastern Conference without a doubt. The top 4 seeds in the West have high expectations. Then you have teams like Phoenix, Golden State, and the Lakers, each led by legendary players who’ve won multiple titles. Throw seeding out the window, those teams are going to believe they can reach the promised land for as long as they’re kept alive.

To prepare for the chaos to come, I want to highlight the key questions and big picture storylines I’m focusing on as the regular season wraps up, starting with the franchise that will dictate my happiness this summer.

The Celtics Are Having One of the Most Dominant Regular Seasons of All Time. Will They Finally Get Over the Playoff Hump?

The Celtics recently hit their rockiest point of the season, losing back-to-back road games to the Cleveland Cavaliers and Denver Nuggets. Each result tapped into the paranoias and fears of the fan base in their own distinct way. On one hand, you have a 4th quarter collapse to Dean Wade, yes, Dean effing Wade, where the Celtics’ crunch time offense settled into its worst hero-ball tendencies. Then there’s the Nuggets game, which raised reasonable doubts about Jayson Tatum going toe-to-toe with a player of Nikola Jokic’s caliber in a playoff series.

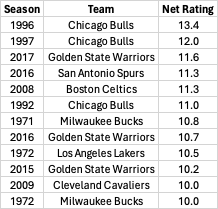

And yet for all these worries, the Celtics are *checks notes* 52-14 with a net rating of +11.4. Only 12 prior teams in NBA history have finished the regular season with a net rating of +10 or higher.

Eight of those twelve teams went on to win the NBA championship. Every team on this list besides the 2007-08 Celtics finished top five in both offensive and defensive rating. Not a single team finished outside the top five in effective field goal percentage. Ten out of the twelve teams finished in the top three in effective field goal percentage allowed. Here’s this year’s Celtics current placement in each of those categories:

The Celtics are checking all the right boxes, and yet have we ever seen a team that pairs this level of statistical success with such trepidation? Even the four previous teams in this elite net rating tier that didn’t win the title faced vastly different circumstances. The 1972 Bucks and 2016 Spurs shared their incredible seasons with other historically dominant teams— the 1972 Lakers and 2016 Warriors, respectively— ensuring that at least one of the great teams from those seasons would fail to win the title. Then you have the 2009 Cleveland Cavaliers, who competed with a 65-17 Lakers team that won the title instead.

Unless one of their Western Conference counterparts ends the season on a tear, the Celtics won’t be accompanied by any similarly dominant teams this season. If you’re seeking a fatal flaw in the Celtics’ armor, there’s one key element missing, an ingredient that all these previously dominant teams possessed. Each team featured either a former MVP, or a player that would go on to win the MVP during that year of regular-season dominance. First Take can stage as many clickbait arguments as it wants to, but the Celtics aren’t going to enter this postseason with a current or former MVP on their roster.

History says that championships gravitate towards the game’s elite players, the ones with MVP hardware decorating their homes. It also suggests that dominating the competition throughout the regular season is pretty darn predictive of championship success. We’ll find out which of these factors prevail in a few months.

Has Zion Been Saving Up for the Playoffs?

Back in 2019, no one would have blinked at the proclamation that Zion Williamson would one day become the best player in the NBA. Conversely, the idea that his career would be derailed by injuries also felt well within the realm of possibility. This was, after all, a man who moves with such force that his foot once burst through a sneaker during a game. But of all places, Zion has landed somewhere in the NBA landscape that I never expected— under the radar.

To be fair, Zion’s current positioning as an NBA afterthought comes with the caveat that chronic injuries have been a major factor in his career. First there was a meniscus tear in his first preseason, forcing him to miss the first 44 games of his rookie season. Then he missed the entire 2021-22 season after having offseason surgery to heal a Jones fracture in his foot. And last season, right when he was putting everything together and leading a promising team, he missed the final few months of the season with a hamstring injury, all but eliminating the Pelicans from playoff contention in the process.

Even though Zion has been relatively healthy this season— playing in 56/67 games thus far— there remains a large elephant in the room. Statistically speaking, he’s never played worse. Here are the categories he’s currently averaging career lows in:

· Total Points/Game (Per-36 Minutes)

· Total Rebounds Per Game

· Effective Field Goal Percentage

· Offensive Rebound Percentage

· Frequency of Shots Taken at the Rim

Shockingly, the Pelicans are performing better with him off the court. In his three prior seasons with the Pelicans, Zion had an on/off differential of +7 or higher, on par with expectations for a franchise player. This season, he’s at -5.7, meaning the Pelicans perform 5.7 points per 100 possessions better when Zion is off the court. New Orleans has a deep, talented roster, with bench units that outperform most teams, but this remains perplexing for a player expected to dictate the future of this franchise.

So what’s the deal? Has the never-ending pile of injuries diminished Zion’s level of peak performance? It’s possible. He’s never going to have the brain-breaking bounce he had at Duke, but something more subtle could be happening here. What if Zion was holding back to stay upright in the regular season? Might we see an optimal version of him when the games start to really matter?

Take his per-game rebounding, split out by the number of opponents contesting the board opportunity:

Whether they’re contested scenarios or not, he’s grabbing rebounds at a lower rate than ever. He averaged less than 4 total rebounds per game in January, which feels impossible for a player with Zion’s physical gifts. Rebounds should be the easiest stat to project— your size often dictates your potential for high volume, and any macro-level decreases in production comes down to effort, or a severe drop in physical form. Then there’s his scoring profile. He’s shooting less efficiently across the board, no matter how closely he’s defended, except for one area. On wide open looks, which the NBA classifies as shots where no defender is within 6 feet of the offensive player, Zion is shooting a career high 72.2%, suggesting a level of opportunism in his scoring patterns that he didn’t rely on in previous seasons.

Despite evidence of restraint, Zion seems to be ramping up at the perfect time, right as the Pelicans prepare for their postseason run. Through January, Zion didn’t have a single month this season where he averaged more than 0.5 blocks per game. That spiked to 1.1 blocks per game in February and is up to 1.3 blocks per game in March so far. He’s averaging 7.9 rebounds per game in March, much more in line with his physical capabilities. The idea of a full-strength Zion Williamson should terrify Western Conference contenders.

Through an analytical lens, the Pelicans are an underrated playoff threat. They have the 6th best net rating in the entire NBA, right beneath the mighty Denver Nuggets and higher than every Eastern Conference team besides Boston. They’re one of four teams in the league with both a top-ten offensive and defensive rating. The supporting cast has made massive strides— Herb Jones might be the premier wing defender in the league right now, and Trey Murphy is catching fire from distance (47.5% on 3s in March). Brandon Ingram and CJ McCollum can give you 25 on any given night.

Make no mistake, this is a team that can make some noise. Should they maintain their current position as 5th seed in the West, they’ll likely face off with the Los Angeles Clippers, whose late-season injury woes are brewing once again. It’s hard to envision the Pelicans beating a seasoned machine like the Nuggets, but a potential 2nd round matchup with a young Oklahoma City team would be very intriguing. If Trae Young and the Atlanta Hawks can make a conference final, you can’t tell me it’s impossible for Zion and the Pelicans.

There’s a large gap between the public perception and statistical strength of this team. The Ringer Odds Machine currently gives the Pelicans the 6th highest title odds in the entire league, yet they have the 15th best odds according to Vegas, below teams like the Mavericks, Lakers and Warriors that aren’t even guaranteed a playoff spot. That’s what happens when you’re the New Orleans Pelicans. Until you make a mark in the postseason, you can’t erase the reputation of being an unserious franchise. The Pelicans drafted one player and one player only to erase this perception. We’ll see if he has the gas in the tank to propel them to a higher plane.

Will the Top Seed in the West Decide the MVP Race?

In the past decade, the race for the NBA’s Most Valuable Player has typically fallen into one of three categories. First is the clear-cut case, when the best individual player for a given regular season also happens to play on the league’s best team. Think Steph Curry in 2015 and 2016, or James Harden in 2018. In the second scenario, a player’s season is so dominant that they can’t be denied the award, causing voters to overlook their team’s relative lack of success. Nikola Jokic’s two MVPs are the perfect example of this distinction. And lastly is when the award goes to the best player on the best team, like Giannis’ back-to-back MVPs in 2019 and 2020. One could argue that James Harden or Lebron James were similarly dominant in those seasons, but team success acted as a tiebreaker and titled those races in Giannis’ favor.

In the past decade, I’d only classify two out of ten MVP races as outliers. Last season, when Joel Embiid was given the award over Nikola Jokic. Embiid had a stellar, MVP-worthy season, but Jokic was on another planet statistically. Many believe that Jokic was punished for his prior lack of postseason success, thus denied the rare honor of winning 3 straight MVPs. This, of course, aged poorly when Jokic went on to win the title anyways last year. Then you have the 2016-17 race, the closest and whackiest race in recent memory, when Russell Westbrook won the MVP by averaging a triple-double for a 47-35 Thunder team. Once again, this did not age well.

I reference recent history to contextualize the unique circumstances surrounding this season’s race between Nikola Jokic and Shai Gilgeous-Alexander . Neither player’s team will finish the season with the league’s best record, eliminating the potential for clear-cut or best-player-on-best-team cases to form. Neither player has separated from the other as the most dominant players of the season per advanced metrics. Unlike last year, Jokic can no longer be punished for a lack of postseason success, so SGA won’t be awarded the MVP as a viable alternative option. And unlike the 2016-17 race, this is only a two-man competition, leaving less room for a split vote.

How far back must we go to find a similar scenario to this year? That’s where I, your favorite box score junkie, come into play. The answer? The 2003-04 season, when Kevin Garnett eked out the MVP over Tim Duncan. At the time, Duncan was already established as one of the greatest players of all time, having earned 2 championships, along with 2 regular season and Finals MVP trophies. This may remind you of a particular candidate this year, whose name rhymes with Rickola Smokic. Then you had a 27-year-old Kevin Garnett, a well established superstar, but a player who had yet to win a single playoff series in his career. Shai is a bit younger, at 25 years of age, but is similarly proven as a superstar (1st team All-NBA last year) and unproven as a postseason performer.

To further the resemblance, neither the Spurs nor the Timberwolves had the best regular season record that season. That distinction went to an Eastern Conference team, the Indiana Pacers. Seeing enough parallels? Ultimately, the MVP award may have come down to the 1-seed in the Western Conference, which Garnett’s Minnesota Timberwolves snuck out by a single game over Duncan’s Spurs. Lo and behold, a close race is shaping up between Jokic’s Nuggets and Shai’s Thunder, who are both tied for 1st with 47-20 records. As I covered recently, I give the Thunder the slight edge to take the 1-seed, but don’t expect Denver to go quietly.

Jokic is the odds-on favorite to win his 3rd MVP at the moment, but I believe this race is much closer than the odds imply. While the Nuggets and Thunder jockey down the stretch for the 1-seed, there’s much more at stake than playoff positioning.

Have the Bottom-Tier Teams Ever Been Worse?

Yin and Yang. All forces of good must have complementary forces of evil to counterbalance them. It’s the guiding principle that governs all things in this mysterious universe of ours. Look no further than the 2023/24 NBA season for proof of this concept. On the good side: scoring explosions, emerging superstars, and the in-season tournament gimmick actually working. The bad: Scott Foster and Tony Brothers continuing to be employed as officials, injuries interrupting historically prolific seasons, and perhaps worst of all, the pathetic performance of the league’s worst teams.

Zach Kram from The Ringer wrote about this season being the first time since 2014-15 that at least three teams have had losing streaks of 15 or more games. Here’s another perspective to represent the futility of these teams: the Detroit Pistons set a record by losing 28 straight games at one point. The Detroit Pistons currently don’t hold the worst record in basketball. That distinction goes to the Washington Wizards, who recently broke a 16-game losing streak by defeating the Charlotte Hornets. The Charlotte Hornets, not the lowly Pistons or Wizards, have the worst net rating in the league at -10.3. And yet the Hornets have more victories on the season than the San Antonio Spurs, who’ve struggled mightily despite having one of the most promising rookies of the century on their roster.

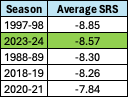

In summary, the bad teams in the NBA this year are B-A-D. So egregious, that I decided to analyze the combined winning percentage and Simple Rating System (or SRS, a Basketball-Reference metric indicating performance efficiency) of the bottom-five teams from every season since 1976-77, when the league expanded beyond 20 teams, to determine the ranking of this group. Here are the five worst seasons based on combined winning percentage:

And here are the five worst seasons based on the Simple Rating System metric, which better accounts for game-to-game performance and schedule strength.

I mean…I knew it would be bad, but this is flat out horrendous. Only one season was definitively worse: 1997-98, when the league was dealing with a talent drought in the aftermath of its expansion in 1995. Both expansion teams, the Toronto Raptors and Vancouver Grizzlies, finished with 16 and 19 wins respectively in 1998. The five worst teams that year each finished with less than 20 wins, led (or trailed, for all my glass half-empty peeps) by the 11-71 Denver Nuggets. All five teams had an SRS of -7 or worse. The prior season in 1996-97 rates as the third-worst based on winning percentage, furthering emphasizing the talent deficiency of that era.

What’s strange about this season’s ill-fated group is that I would hardly describe this era of NBA basketball as talent deficient. On the contrary, many of the league’s worst teams are brimming with young talent. The Spurs have Victor Wembanyama, in the midst of one of the best rookie seasons of all time. Players like Cade Cunningham, Brandon Miller, LaMelo Ball, and Shaedon Sharpe all have star potential, despite featuring for the league’s doormats. We’ve seen plenty of less talented teams find a way to squeak out 20-25 wins, so it’s puzzling to see many of these teams project to fall short of that mark.

Take another look at the worst seasons filtered by SRS and you may notice another interesting trend:

Four of the six lowest-rated groups by this metric have occurred since the 2014/15 season. The league’s worst teams are losing by increasingly larger margins on average than in previous eras, which adds up when you factor in the prevalence of the 3-pointer and higher league-wide scoring outputs. Note the following statistical increases since the 2014-15 season:

· Points per game has risen from 100 to 114.8, which is the highest scoring average since the 1967/68 season.

· Pace has risen from 93.9 possessions/game to 98.8 possessions/game.

· Effective Field Goal Percentage has risen from 49.6% to 54.7%.

The average NBA game features more possessions and more sharpshooting, leaving more opportunity for bad teams to get torched on the score-line. Notably, the effect on raw winning percentage has been less drastic. Only 3 of the bottom 8 seasons based on winning percentage have occurred this century. It’s taken until this season for the impact to feed into the loss column in a more pronounced manner.

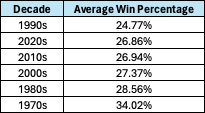

Does any of this mean anything on a macro-level? Probably not, but we can anticipate an effect when the league inevitably expands to 32 teams, much like we saw in the 1990s. If we aggregate this analysis and look at the progression of bad-team performance by decade, you can see that the 2020s have largely mimicked the preceding decades from a winning percentage standpoint:

The NBA will never again match the competitiveness of the 1970s and 80s, which featured less teams and thus a more even distribution of talent. The 90s suffered from the expansion years, and in the current century, bad teams have settled into a consistent 26-27% winning rate on average. The drop to 22% this season is more than likely an outlier; a rare combination of rebuilding teams, razor-sharp offensive efficiency, with some coaching malpractice sprinkled on top. Or maybe it’s harder than ever to win an NBA game, given the ruthless amounts of star talent on so many rosters. As the professional game continues to evolve through the end of the decade and beyond, it’s a trend worth keeping an eye on.

*All stats are from Basketball-Reference and Cleaning the Glass unless otherwise noted

great work, DL!